This is Cecil Frances Knight's story, written in his own words only a few years after the end of the war.

Where possible, it is illustrated with contemporary photos.

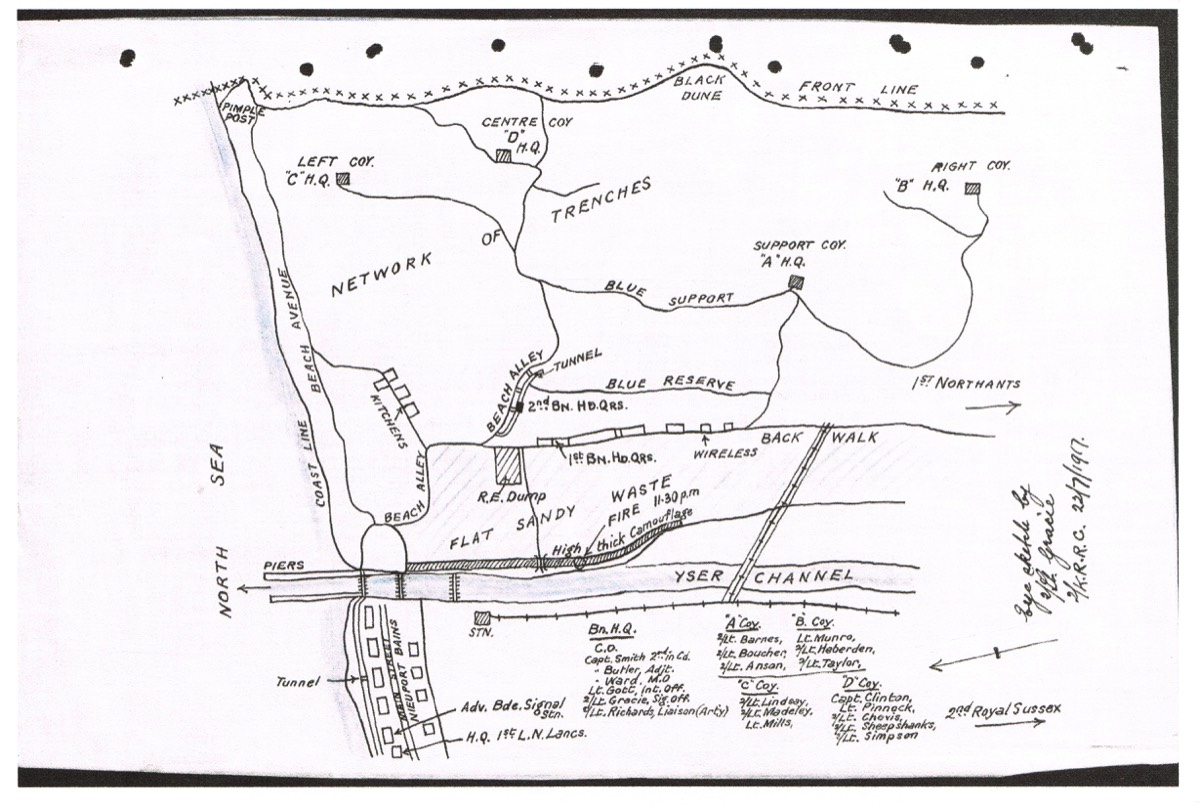

However to get along. On the night of 4th-5th July 1917, after laying in reserve for a couple of days, we crossed the Yser canal and went up the line to relieve the Jocks.

(The Jocks were the Black Watch who had been in the trenches in a support position at the beginning of July but who then moved further back down the coast line. Interestingly, the war diaries of the Black Watch record the fact that they were relieved by the KRRC but the KRRC diaries make no mention of relieving the Black Watch)

The relief was carried out, the only incident being a cursory bombardment, which delayed No.5 platoon, necessitated I and a pal going straight to No.5 fire bay and going on sentry. We were relieved about midnight, having been encouraged by the Jocks - 'Thank God you've come' and the fact that Jerry's line being only 25 yards away and making a half circle round ours, he could enfilade us with machine gun fire very effectively.

About one o'clock, I and half a dozen other recruits were called up to go down to the Company Sergeant Major's Headquarters to fetch spades. It was moonlight and the sand dunes looked quite peaceful. (The photo above shows CFK and comrades in the infamous sand dune trench. CFK has an 'x' over his head. Who took this photo, and how did it get into the family album?) Now and again a well-fed rat jumped out of the light. We arrived at Company headquarters, bagged spades and started to return. Half way along, Jerry, who had been watching, opened fire with Whizzbangs, My first warning was a little chap in front of me entangling himself in some (barbed wire) hurdles, and going nearly mad in his efforts to clear himself, as the crescendo of shells shrieked over. Presently he got away and I followed him hotly along the already battered trench.

(Map from KRRC War Diary)

Soon the fire became too hot and instinctively, we fell flat. Before us along the trench was a crashing wall of flame. It lifted in an instant, a moment later it would fall again upon us. We dashed into the smoke and a minute later we reached the dug-out. I stopped and waited for my pal, but he did not come. The sergeant came and dragged me into safety. Two minutes later my pal fell in, exhausted, through the other entrance. Later on, a man with shrapnel in his chest, staggered in.

On the night of the 9th-10th July, we did a bombing raid. (This is the raid with the Rhodesians referred to in the History section) Fifteen men in sandbags to capture a prisoner. It was a beautiful sight. Our barrage was as straight as a die on their firing line, a solid wall of flame, flickering on the smoke cloud above. A yard or two over our heads, sung our six pounders. Overhead hummed the planes, while right back for miles behind Jerry's land, the sky was filled with many hued lights. From the close red distress signals, to the vivid blue bubbles of fire over Bruges.

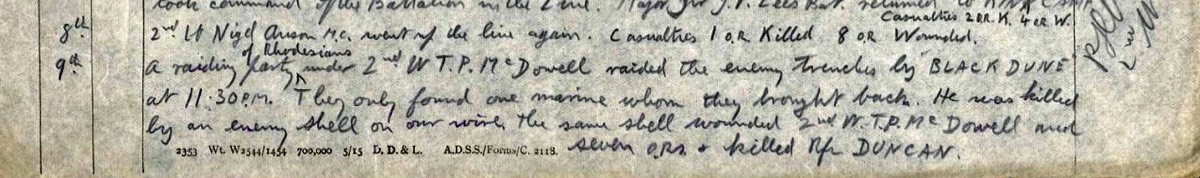

Except from the War Diaries of the KRRC for 8-9 July - "A raiding party of Rhodesians under 2nd Lt T P McDowell raided the enemy trenches by BLACK DUNE at 11.30pm. They only found one marine who they brought back. He was killed by an enemy shell on our wire, the same shell that wounded 2nd Lt T P McDowell and seven ORs and killed Lt. DUNCAN"

The night passed in anxious watching. And the morning of the 10th July broke brilliantly. Spasmodically our trench mortars spoke - we cursed them. Presently Jerry's guns answered and our usual visitor, a shell 20 yards to the rear, said 'Good Morning'. We salaamed to the ground reverently. Unfortunately, Dean and I were sitting on a plank that being supported in the middle only, acted as a see-saw. And if one, in his haste to bow to Jerry's salutes, rose before the other, the last one tumbled into the sand.

Sometime later, after brekker (a parcel I had, supplied salmon and cucumber!), we had news that the sergeant major who should have relieved our platoon officer, refused to leave his dug-out, wherein he was weeping profusely. So it happened that our officer, learning that the left Lewis gun post had been buried by a Minenwerfer (infantry mortar), rushed up for volunteers to dig them out. About half a dozen of us responded and he led the way. On reaching the post, Jerry saw us and dropped a few heavy shells. Two or three panic stricken men rushed past me. After a breathless pause, I said to a man' It's no use leaving 'em buried - come on'. He said, 'Right you are', and off we went. On reaching the scene of the downfall, I found myself alone. Bodies were lying about, blown to pieces and steaming. The officer was still alive. 'For God's sake, a stretcher', he gasped. I sent for one. Dean and the sergeant crept up, and we bandaged him, and carried him back to the communication trench, where a disused burnt out dug-out was situated. We put him in the entrance, and I looked out for more Minnies (trench mortar shells). Not being boss-eyed, however, I could not look at the doctor's doings and the enemies at one and the same time.

So a Minnie dropped about twenty yards away without warning. A moment later I felt a heavy thud in the neck, and was twisted round and thrown to the ground. My first thought was to see if I could shout, and finding it impossible, I gave up the idea of oratory. I was helped into a hole and bandaged. I was nearly suffocating, my breathing was painful and insufficient. My pal came to me, and at my request, voiced in the pleasing tones of a rattlesnake, and nearly fatal to me, I asked him to get my shaving brush which belonged to my father, and I knew he would not like lost. He wished me astonishing luck and I had it. A piece of shrapnel had entered and passed to the other side of my throat only just clipping those vital spots, the artery and the windpipe. The piece should have killed me, and in the light of later events, I blame it for its inefficiency.

Later, the bombardment lulling a little, my pal helped me out to go to the dressing station. I had not taken half a dozen steps before I choked. In my rage at suffocation, I struck Hodges a blow that nearly knocked him down. I couldn't stand him fiddling about round me. At that moment with a roar of thunder the greatest bombardment of the war, opened. I about-turned, and was carried fainting into the dug-out. I remember clawing the earth in my strain for air, and then I went off. My pal said I appeared to remain conscious for a long time, my eyes protruding from my head, and my face blackened from the struggle to breathe.

The Doctor was amputating the officer's leg and could not attend to me, so he shouted directions to Hodges, who was frantic. At last he had come to me, when he removed the bandages and applied artificial respiration. I remember drawing a most delightful cool breath of air as I came to, sometime later. I don't think I have ever enjoyed anything quite so much.

The curious thing that remains in my mind, is that I was so near death, perhaps a few seconds, if the doctor had not come. I saw nothing of the Hereafter. Unlike my friend Jenkins, who dying from dysentery, saw and heard his mother calling. He was just going to her arms, when they shook him and kept his spirit living.

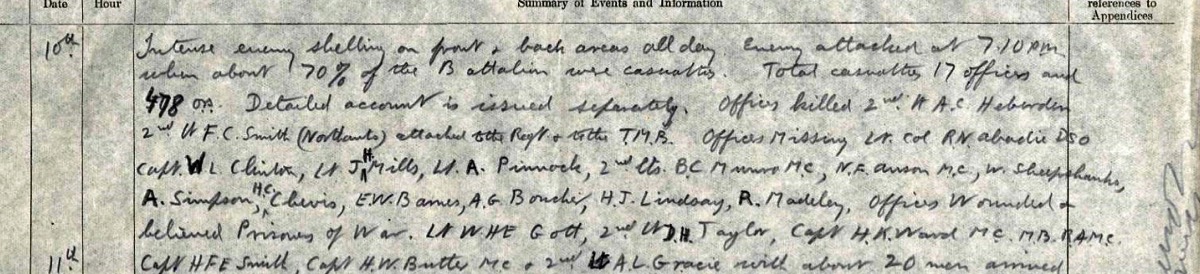

Except from the War Diaries of the KRRC for 10 July - "Intense enemy shelling on front and back areas all day. Enemy attacked at about 7.10pm when about 70% of the battalion were casualties. Total casualties 17 Officers and 478 ORs. Detailed account issued separately. Officers killed 2nd Lt A C Heberden, 2nd Lt F C Smith (Northants) attached to the Reg't and the T.B. Officers missing Lt Col R N Abadie DSO, Capt W L Clinton, Lt J H Mills, Lt A Pinnock, 2nd Lts B C Munro MC, N E Anson MC, W Sheepshanks, A Simpson, H C Chevis, E W Barnes, A G Boucher, H J Lindsay, R Madeley. Officers wounded and believed Prisoners of War Lt W H E Gott, 2nd Lt D H Taylor, Capt H K Wood MC MB RAMC"

During the day, the blood continued to trickle down my chest until my shirt and cardigan were saturated. Three times the shell hit the entrance to the dug-out - and I was nearest the entrance for I had not enough strength to crawl further in! I remember each time, replacing Hodge's tin hat upon his head, as it rolled in my direction. I remember too, vaguely wondering how the man opposite had three legs. For hours I thought over this freak, until I remembered the officer's leg which had been thrown aside after dismemberment.

The last shell, an armour piercing naval heavy, buried half of us. Then in the reek and blackness, the elite showed themselves up. They rushed round, colliding, shrieking, moaning. At last the smoke and fumes cleared and showed small apertures in the roof. Our gallant corporal ('ought one, yer blighters !) led the way. At the top, he found it too dangerous to get out, and too dangerous to stop in. So he blocked the way. The men behind shouted and fought. 'Pull him down they cried'. He was duly pulled down, with a shriek like a woman being murdered. I tried to follow them, but was too weak, so left alone, buried I crawled to the burnt out entrance and found it had been partially cleared by the explosion. Half an hour later I was in the front line trench. What a mess it was in. I found it impossible to go along so I crawled on top. Pop-pop-pop, welcomed a machine gun. I could not hurry, so didn't. Further on a chap called me all the fools he could, but I could only wobble my head and grin like an old dog, as I crawled along. For the next couple of hours I sat on the fire step with a sand bag over my knees for protection - how we stick to life! – and watched the sun sink slowly in the heaven.

Jerry was then cutting the barbed wire with shrapnel. Suddenly the barrage lifted and I heard, 'Up rouse'. And a squadron of Jerrys swinging their bombs, (most likely grenades) inviting me to arise. Not knowing them personally, I smiled a sickly smile and sat on. One of them aiming a bomb, caused me to move, and after moving in a whirling cyclone for a minute, I sat down again. Some men came out of the concrete shelter nearby and said 'Put your hands up yer fool'. I was not up to physical jerks and couldn't. Dean came along the trench like the man he is, he had stuck to his post to the last.

No.5 bay was not struck until 3.30 pm. It was a lucky bay. I'm sorry I left it, however, he helped me up. Half way across no man's land we dropped in to a shell hole, not meaning to go through our own barrage, paltry as it was, or to be captured so easily. Down came an aeroplane, 'pop-pop-pop' it reminded us. 'Sorry', we chortled and went on.

Then came a terrible march - about three miles to the rear of Jerry's lines. For the first part Dean, the good old chum, helped me, and I was so intent on moving my feet that I banged my face on some horizontal girders, so he tells me, but I don't remember it. But I remember the murderous torture of that march, stumbling, gasping, cursing our way to the dressing station.

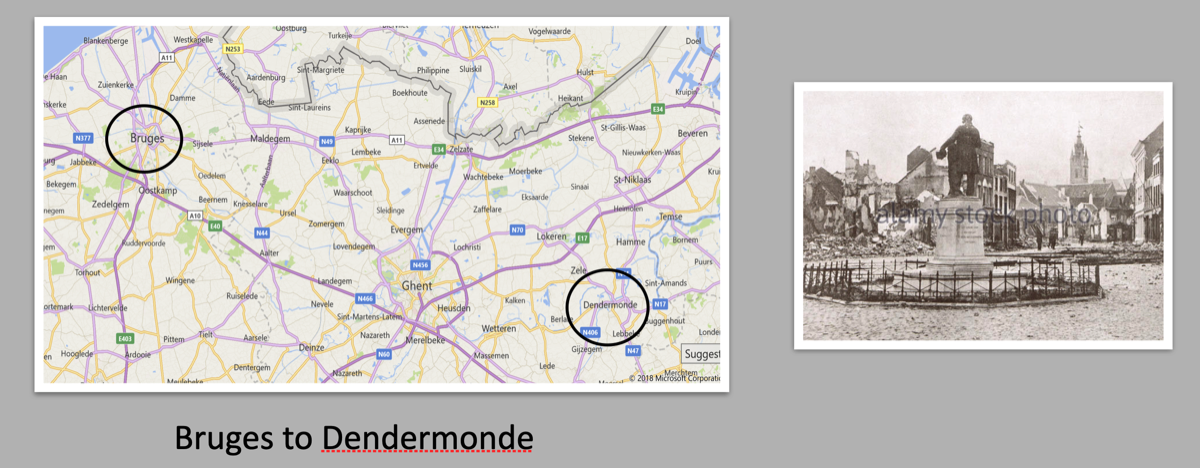

I was somewhat fresher at the start, for the rest on the fire step, and the bleeding had stopped, having been again bandaged. I arrived in hospital (in Bruges, above) on Wednesday evening, having been wounded, and without victuals for 36 hours. My only thought was water. 'If there are lakes and lakes of water in Germany I don't mind' I kept saying to myself. I was the first to be operated on, and it was then that I discovered my miraculous escape.

The doctors liked me, I amused them by trying to see my wound in a steel mirror. But my face, Oh Lord, a dirty greeny grey, with black muddy rims round my eyes nose and mouth. No wonder I amused them. The doctor questioned me in French. My pronunciation must have been interesting, a metallic gasping grate. 'Il me trouble - de respirer. Pas assis du vent !'

From that time my thoughts and mode of life changed. I realized that I had been saved, perhaps to do good, and I tried in thought and deeds to be a Christian. God knows how hard it was. But I am satisfied. My comrades loved me, and the Germans respected me. One old German would let no one else touch him - he gave me two marks when I went. An Englishman thanked me for saving his life. I was content.

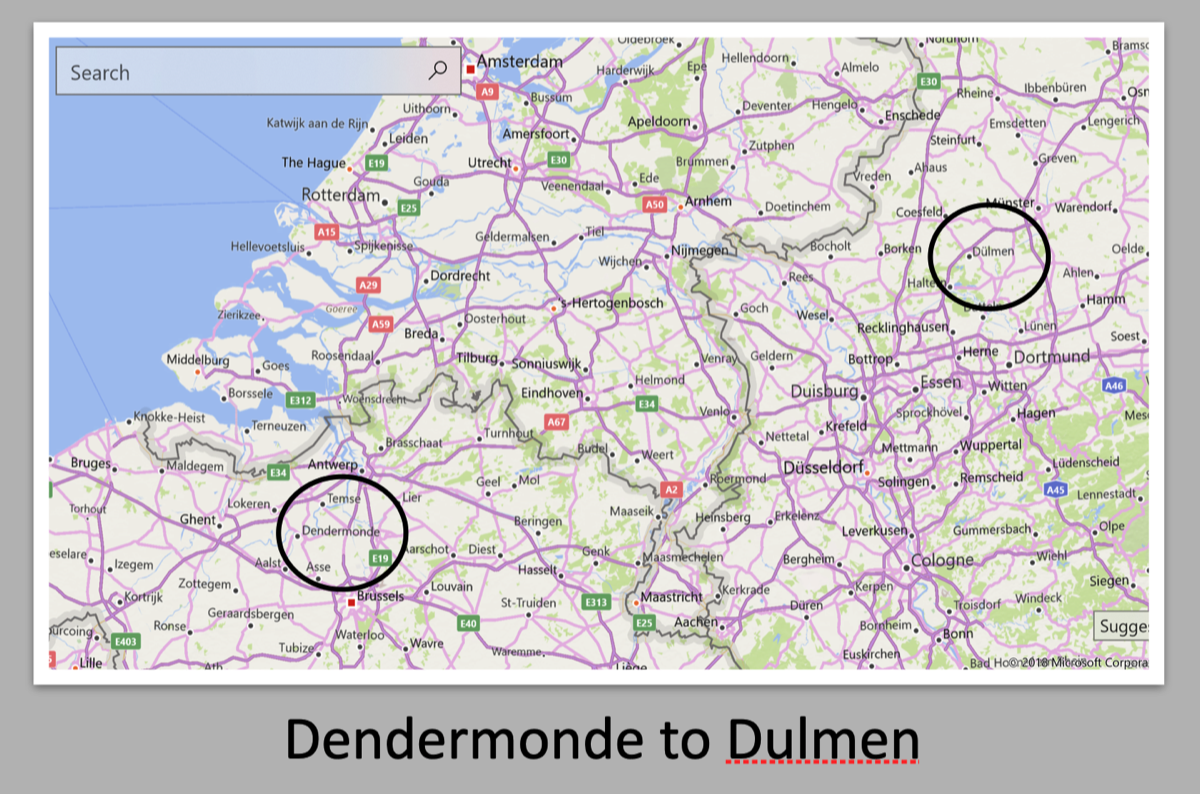

On the 20th of August I went with a little friend of mine to Dendermonde (Belgium) (below). I shall never forget the entrance to that hole. In the shell-shattered town, the cowed inhabitants shook their heads mournfully at us, yet seeing our bold and smiling bearing took courage and smiled. A girl I noticed was smelling a rose. She smiled and I held out my hand for her to throw it to me. The look of fear on that girl's face! I remember it now, as she pointed to the swine faced gendarme, escorting us. But the shock was when we entered prison. All around stood our old comrades, no longer human, but skeletons in rags. Their eyes fishy and bloodshot, their whole bearing cowed and beaten. They beckoned for cigarettes. My God the Englishman is a queer being. This place was a clearing house where prisoners were starved before being exhibited to the German public as newly captured men.

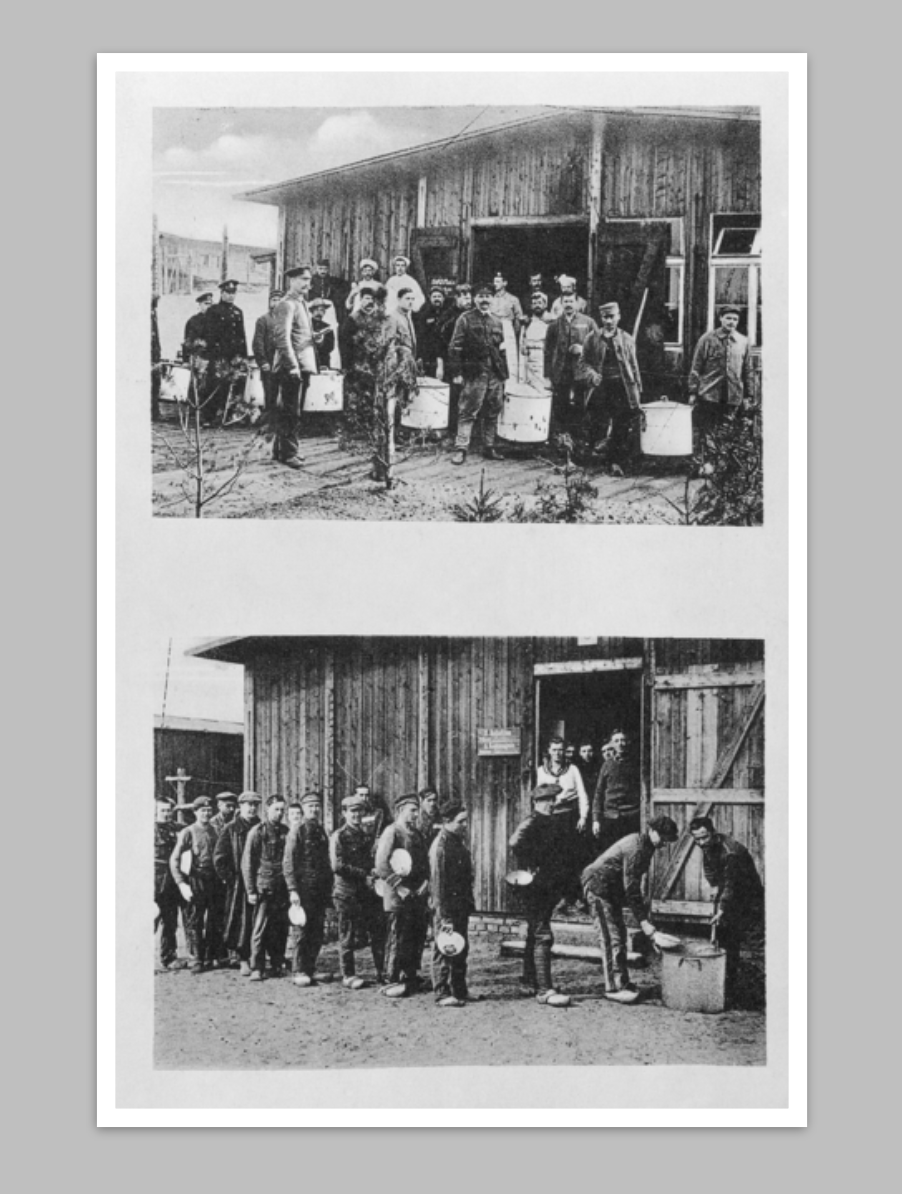

I only stopped there for two weeks, but it was enough. The food consisted of:- a slice of black bread, a bowl of mangy coffee without sugar or milk.

Midday, a bowl of cabbage soup - 60 or so of spoonfuls of pure liquid and six or less of sediment- greens, field peas and the like - proper hog wash.

Evening, more soup but weaker. The fighting for this muck was terrible.

Before I came the men used to line up for it, and those at the back would think there would be none left and would creep up, and in the end the soup would be over turned, and the men like hogs would go down on the ground and lick it up. Once, in my experience, the soup was made of stewed pear juice, field peas and bad fish roe. It stunk and, our stomachs, eager as our stomachs were they, refused it. Yet there were some swine, sunk lower than the worst vagrants in these isles, mopped the filthy stuff up and fought for more. The bath was overturned finally and the dregs were licked up. The only amusements of the place was supplied by myself. I had a po-chamber to get my soup in and as it amused the boys, I did not exchange it. It was truly made to contain stronger liquid the Dendermonde soup. Apologies!

We left there in the early morning of 2nd September. Most of us missing the issue of soup, which replaced the coffee. We also had a slice of bread each, which my pal and I saved for the journey. Lord what a journey it was! Packed together in cattle trucks, lousy, cold and starving. We had one drop of soup in 24 hours. In our truck, a German's bread was pinched and Etheridge and I turned suspicion on ourselves by eating the bread we had saved. However, all things come to an end, and after a five miles march, staggering and dizzy, we were given soup.

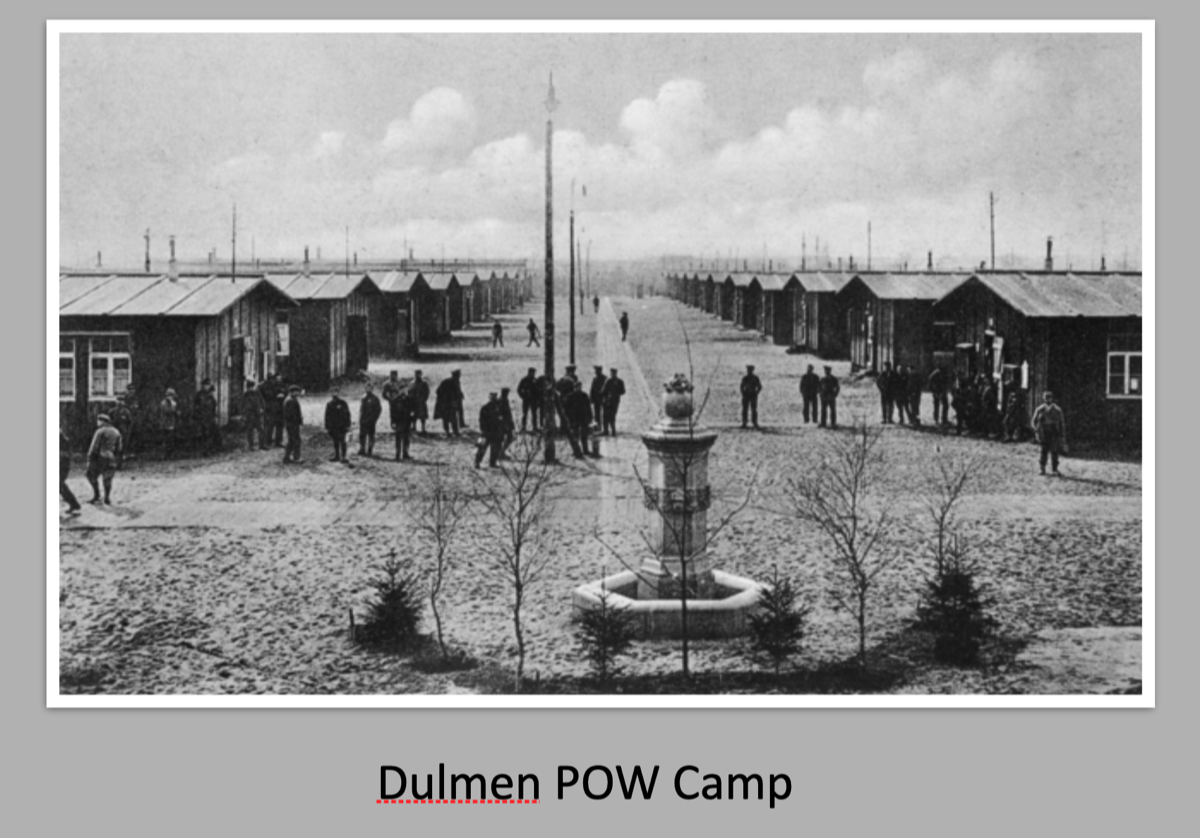

Dulmen was a camp of inoculation. The fare was slightly better but the benefit was lost in fighting typhoid bacilli. They also gave us a scrap of calf lymph, the only meat we got in that establishment.

(Right - Prisoners queuing for food at Dulmen)

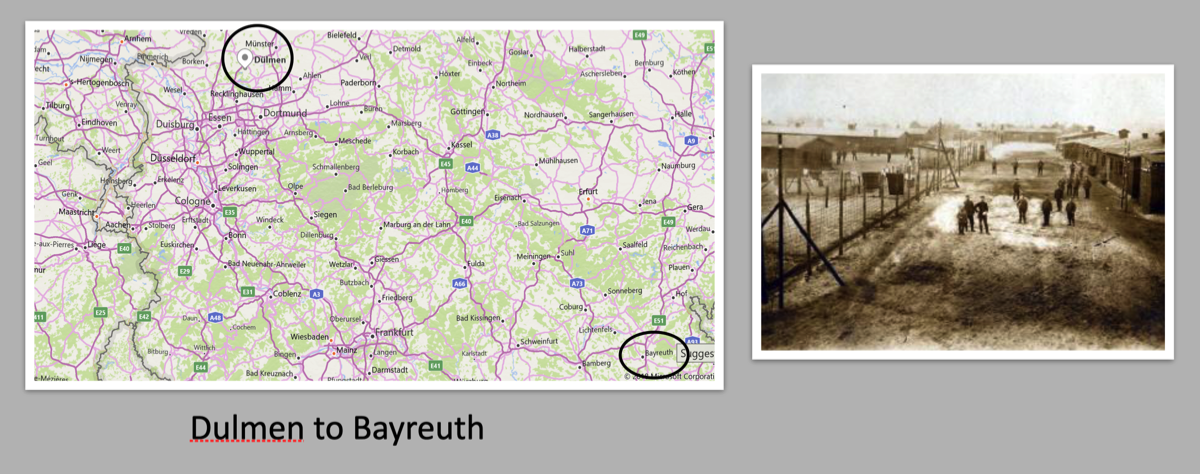

Then came another train journey, but this was better as we had soup every 12 hours. It lasted from early on the 17 September until we arrived at Bayreuth, Bavaria, (Below) on the early morn of 19 September. One lot of soup, cabbage stalks, was so thick that I got chronic indigestion and had it badly right down the valley of the Rhine.

Bayreuth then saw us for three weeks, when we were bundled out to work. This time I took raw mangel-wurzle and nearly made myself ill. For nine months I worked on the farm doing as little as I could and doing as much harm as possible. On my birthday (27 April) I was thrown into prison,(Amberg) (a damp filthy two horse stall with no light or ventilation for 14 days. The food was a piece of black bread and water (in abundance).The sanitation, being internal was horrible - worse than Dendermonde.

Later on I got myself another spell of 15 days, but got a reprieve after 10 days because I puffed up a German officer by addressing him in French, which if one is polite and courteous, always puts them in a self-satisfied and complacent mood. I, however narrowly escaped the sand sack for three hours per diem for making fun of a Feldwebel (German N.C.O.) - very haughty person. But my wit saved me. I asked to speak to an officer, which he would not. Neither would I carry the sand sack (56Ibs).

After this I did no more work for Germany. I went to four other farms but did nothing, pretending to faint and refusing all hard tasks to avoid work. I went hop picking, but by strategy, I got back to camp when I should have gone potato hoeing! With me, I had acquired over half a hundred weight of potatoes, several beetroot and turnips.

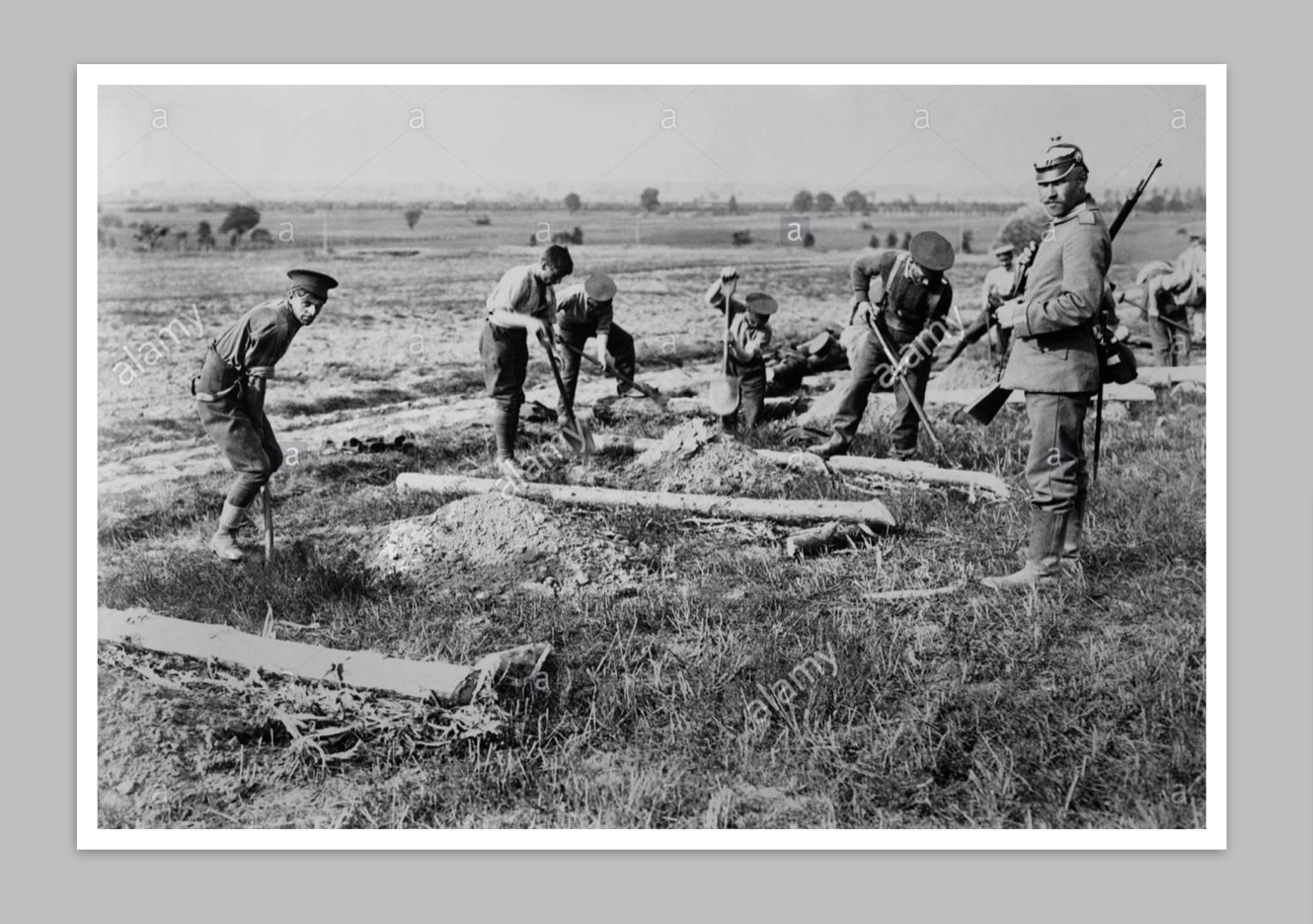

(Left - Prisoners doing agricultural work)

Jenkins and I danced muchly as he welcomed me home. Good job I was not caught, else I would have had another 14 of the best. Finally, after learning all things that one who lives by makeshifts and his wits must of necessity learn, I was sent to work.

Before continuing I should like to review those six long weary months of idleness, with nothing to do but to keep our little household 6ft by 6ft, in order. And a neat comfortable little home it was, with ornamental cupboard and a shelf of polished crockery and underneath the lamp apparatus - a crude piece of rag dipped in some bacon fat. About a foot above my bed, I had a rack containing a pipe baccy and matches, and decorating the whole wall numerous photographs, which served to remind me of the good time that was coming.

During the long hopeless days, our thoughts used to be very busy. We evolved, like Diogenes, a curious philosophy our thoughts were not bitter, just probing. We looked for theory that would logically explain why so much misery was permitted on earth. I and a friend would argue for hours on theological points He prided himself on being a materialist, but he wasn't. He believed in nature. Many of the ideas evolved during this time of dreams remain with me yet and I believe them. They are no more sacrilegious than spiritualism.

However, to continue, after a medical examination, we were sent out to work. But I worked not. And I got 14 more days arrest. - this time in a proper prison. Having good warning, I had 2lbs of bacon sliced wrapped in a towel about my waist, tobacco in my socks, money and matches in my lining, and my pipe where I can't mention. Thus equipped, I chipped the searcher in English in a most engaging manner and did my 14 days in a cheerful manner.

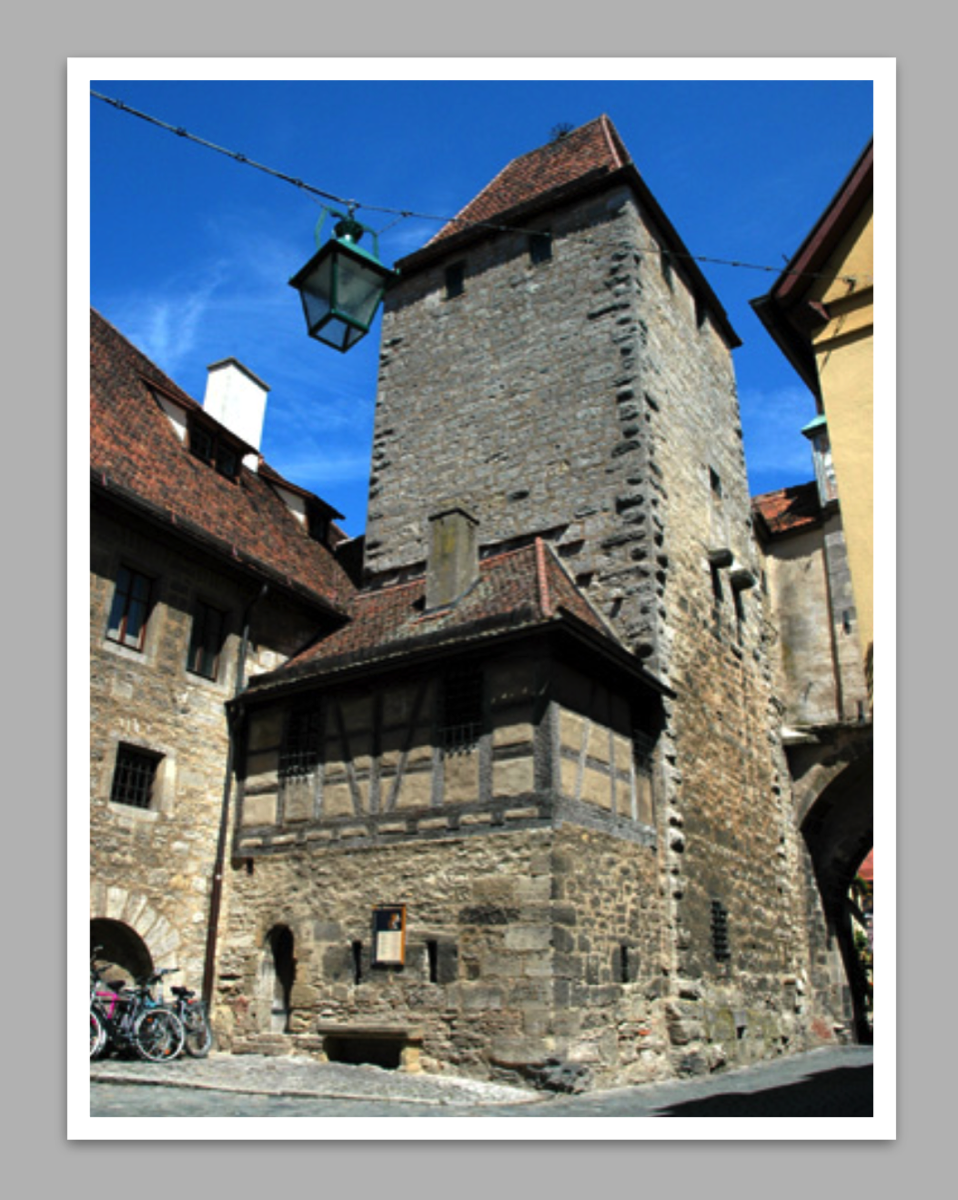

Old Rothenberg prison

Above - British PoWs at Bayreuth?

When I came out on the 14th of November 1918, the war over, and I knew it not. I asked for a doctor but was roughly sent to work again. I fainted on the road in a splendid manner and made the guard carry the box etc, and me! I worked not and was referred to the doctor. I ate about a quarter of a pound of soap to give myself heart disease. The doctor said, 'Marvel you are still alive - return to barracks'.

On the journey back, I had to sit out in the snow, so they wouldn't see me laughing. The camp was in a terrible state when I arrived, so Nobby Clark and I started to organize it. So that soon, as every man came in, he was supplied with blankets and a bunk etc. The German officer disregarded, and rightly, our weaklings of NCOs, and communicated his wishes to me. I never want to look after such an undisciplined rabble again. It was a thankless job.

The Soldiers and Workers Council offered to arm us and let us fight our way out, but fortunately the officers moved first and we started for home. (this was an organisation established in June 1917 to support the Russian revolution. A similar group was formed in Germany in 1918 to encourage a German revolution)

The final lap through France was a disgrace to the British army. More men died, more brave hearts were beaten, during those few days, than during the whole of our captivity in the hands of the enemy. It only confirms the theory, nay belief that the war was won, not by the British army administration, but in spite of it.

Long live the undaunted spirit of humour that rules a Tommy's heart, to let him fight the devilish cruelty of his own leaders, and beat the enemy to his knees as well! "

Signed C.F. Knight. 7.10.1919.

Footnotes

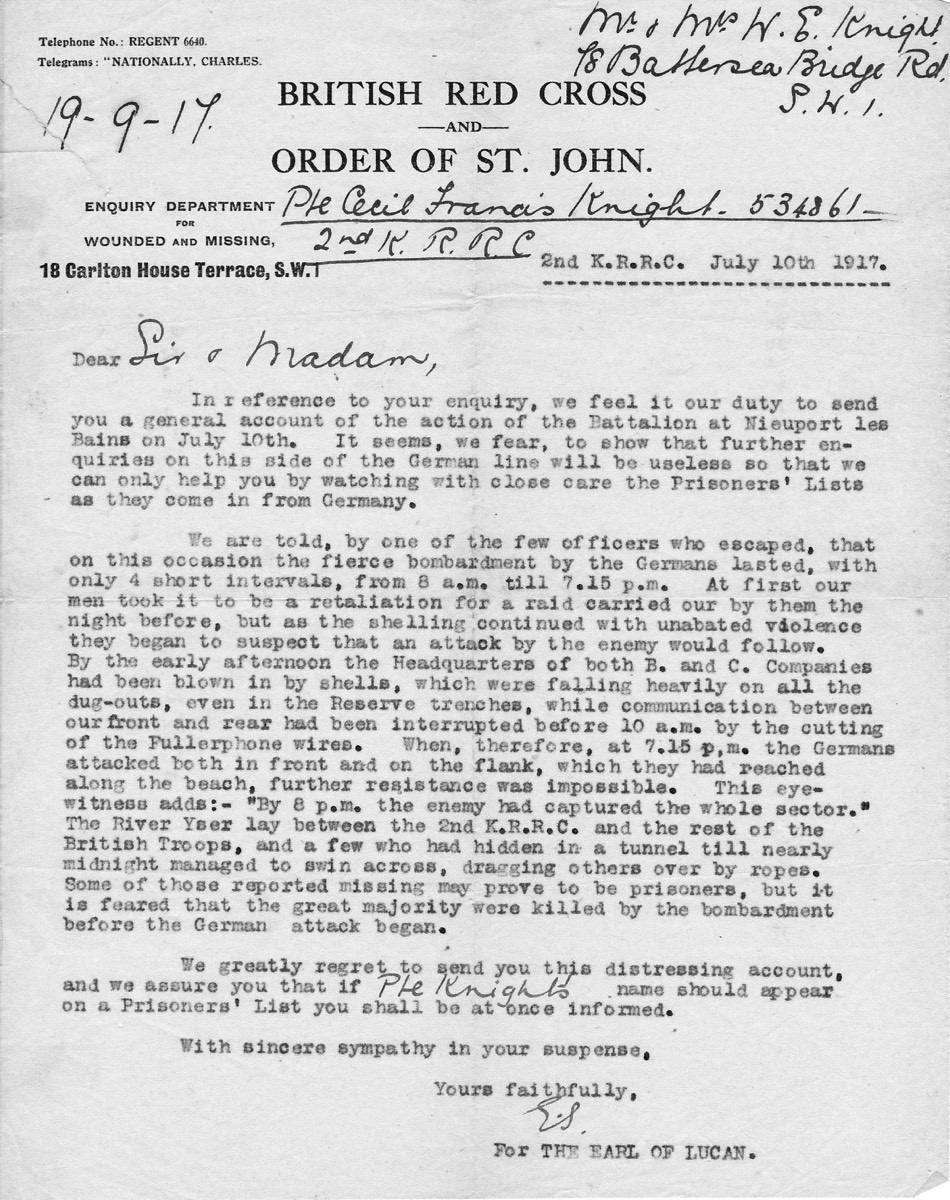

CFK did not arrive home until early on Christmas Day 1918. As far as we know, his family were unaware that he was coming home, they only knew that he was 'Missing in action' by virtue of a Red Cross letter sent 15 month earlier. (Left)

The first paragraph says "In reference to your enquiry, we feel it is our duty to send you a general account of the Battalion at Nieuport les Bains July 10th. It seems, we fear, to show that further enquiries on this side of the German lines will be useless so that we can only help you by watching with close care the Prisoners lists as they come in from Germany."

This was followed by a description of the battle, and concludes that "We greatly regret to send you this distressing account, and we assure you that Pte Knights name should appear on a Prisoners' List you shall at once be informed.

With sincere sympathy in your suspense"

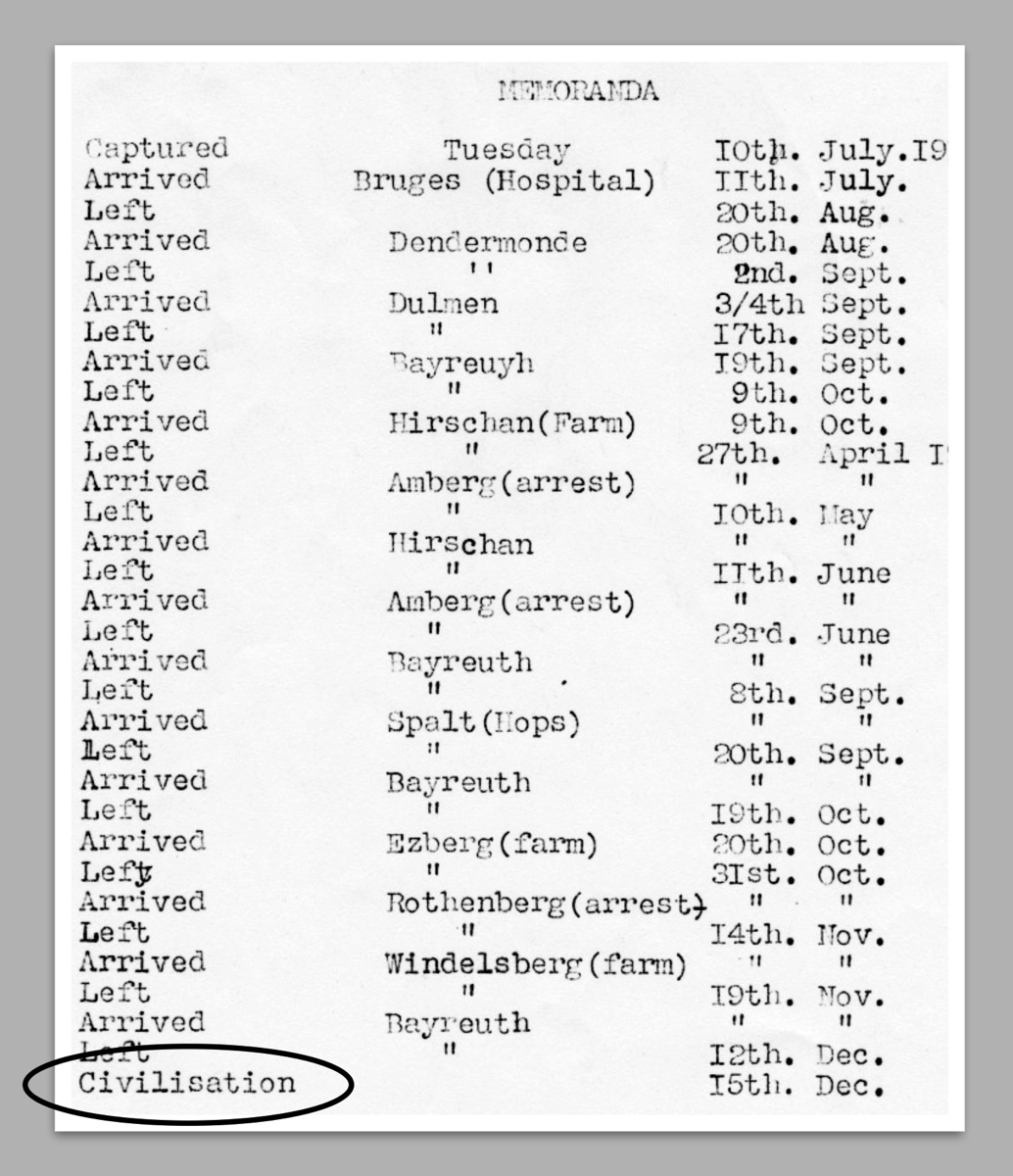

Right - This is a list of the places that CFK was sent to as a PoW, as recorded in his Paybook.

There are a few places that aren't mentioned in his account, mainly farms that he was sent to.

As you can see, he arrived back in the UK on December 15th ('Civilisation' in his list), but the authorities refused to release the ex-PoW's until the day before Christmas.

It is worth noting that CFK's experiences on the battlefield, during his subsequent imprisonment, and on the horribly mismanaged journey home had quite a detrimental effect on him. He suffered from Traumatic Stress Disorder for much of the rest of his life, with bouts of depression that affected the whole family interspersed with times when he was 'as high as a kite', which wasn't much better.

Memorial in Nieuport, Belgium (now Nieuwpoort) to all those missing in action in operations on the Belgian coast between 1914 and 1918

Acknowledgements

Many of the pictures used to illustrate this history are stock images from a wide variety of online sources.

Thanks go to:

14-18.bruxelles.be

Alamy.com

Andrewsarchives.com

Codex99.com

Flickr

Geograph.org.uk

Google Maps

Imperial War Museum

KRRC Archives

Longlongtrail.co.uk

NZHistory.gov.nz

PeriodPaper.com

Scrapbookpages.com

www.14-18.bruxelles.be

www.awm.gov.au

Wikipedia/Wikiland

www.worldwar1postcards.com